By Glenn Ashton · 8 Jul 2013

Media coverage of the Obama-crew’s flash-mob blitz of South Africa showed the extent to which we have allowed ourselves to be policed by a force that continues to display apartheid era tactics. While Obama was touring Soweto legal demonstrators were treated to percussion grenades and teargas for protesting too vigorously.

South Africans have a proud history of peaceful protest, from the women’s march on Pretoria in the 1950s, the pass protests into the cities across the nation in 1960, The student demonstrations during the 70’s, right through to the UDF marches in the late 80s and 90s that shut down entire cities; violence was inevitably triggered by police excess.

Have we lost our old protest pluck? Have we become cowed by the Marikana approach to crowd control? Were we to don a Guy Fawkes mask, in solidarity with protestors around the world, we would risk arrest for concealing our faces. Instead we meekly allow ourselves to be filmed by the police, passive before the global surveillance state.

People protest because they perceive that government is unresponsive to their concerns. Instead of democracy delivering us a two-way dialogue between rulers and the ruled, we remain governed by an autocratic oligarchy that screens the input from below. The only way to get results appears to be violent disruption, with the inevitable violent retaliation. Protest has become a last resort; it is no longer a mass statement and if it is the message has been lost.

In order to be heard we don’t make phone calls, initiate dialogue or write letters; those approaches are just ignored or denied. Instead we engage in “service delivery protests.” These are then dealt with by an understaffed and poorly trained police force who have far more in common with the protestors than with the authority they represent. But because of the polarization they are forced to over-react in the only way they know how.

A dual trend has emerged, where the poor protest by burning tyres and spreading shit, while the middle class attempt to hold the government accountable in the courts. It is far easier to govern the divided.

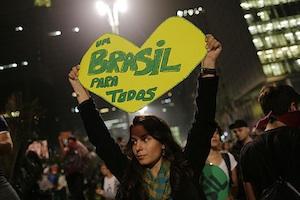

In Turkey and Brazil, protests have erupted against similar cross cutting issues that affect us all – poor infrastructure, expensive transport, education and food, aggressive policing, non-responsive or repressive government, and so on. These issues impact all classes except the most insulated of the oligopoly, the 1%. Yet in South Africa protest has largely become the domain of the poorest and most disempowered. The cross-class solidarity apparent during the struggle years under the UDF has faded away.

In Turkey and Brazil the middle classes relate far more closely to the poor than to the oligopoly. In South Africa the converse is true. Turkey and Brazil have recently begun to emerge from exceptionally unequal social realities, especially Brazil, which until very recently was on a close par to South Africa. Young Turks see freedom emerging across neighbouring Europe, while theirs diminishes. Yet the economic instability of the last few years has stalled this upward mobility, reflected in far more broadly representative protests.

On the other hand South Africa remains so socially polarized that the huge part of the problem. At the same time middle classes identify more strongly with the rich, largely fearing the anger of the poor. Consequently there is scant class solidarity in protests against the status quo.

Yet systematic inequality remains and even increases. While the middle classes may engage in throwing nothing more threatening than a legal letter or a writ at authorities, the poor often only have stones and barricades. The common, fundamental problems related to a lack of open and participatory governance remain unaddressed.

Conventional academics respond that we have the right laws in place. The problem lies in their implementation, essentially our government is inefficient. But is this really the case?

A closer reading of our laws reveals that, despite the politically correct preambles packed with left-sounding phrases like ‘social inclusion’, ‘consultation’ and ‘transformation’, the interpretation and implementation of the fine print is as right wing as Margaret Thatcher’s regime. The economics driving our government is out-dated and discredited. Despite promises of change this has continued, if not worsened, under Zuma. As political economist Patrick Bond noted back in 2004, the ANC talks left and walks right.

The DA was quite right to woo Trevor Manuel – his economic position is far closer to theirs than that of the ANC allies, if not the ANC itself. But why should he shift to the losing side when he writes World Bank inspired government policy, having the economic power of a de facto president? As Ronnie Kasrils recently wrote, the revolution was sold out to the neoliberal compromise.

Neoliberal policies disadvantage the poor and the middle class at the expense of the rich. The middle class is burdened by debt and taxes (both of which the rich are able to avoid) while the poor are excluded from educational and economic opportunities.

The minimum farm wage is a concern that demands collective resolution. Unmet municipal requirements, be they roads, houses or toilets, must be honoured for all. Developers and industry cannot be allowed to march roughshod over community wishes or environmental concerns. These are each symptoms of the same malaise, signs that our society has not sufficiently transformed to deliver the changes promised by the new dispensation. The laws may have changed but the implementation has not.

This logic makes it clear why we fail to articulate the very real structural realities we collectively face; the middle class, working class and poor alike are threatened by similar dynamics. Local economies are destroyed by supermarket chains, which suck money out of communities into the trickle up economy, while street traders are harassed and persecuted.

No coherent voice has emerged to voice informed opposition to the new economic order. The ANC and DA are as difficult to differentiate as the Democrats and Republicans in the USA. The politics of globalization remains fundamentally identical for everyone in a globalised world, whether they live in the USA or SA. In fact the over-reaction of the authorities and cops to the occupy movement in the US is not dissimilar to policing experience in Turkey, Brazil or here. Kragdadigheid has gone global.

The last truly inclusive protests I can recall in South Africa were those at the otherwise dismal World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg in 2002. Here the ANC maligned “ultra-leftists,” including the Anti-Privatisation Forum, the Anti Eviction Campaign and the Landless Peoples Movement joined forces with environmental activists and intellectuals from around the world in a march from the slums of Alexandra to the skyscrapers of Sandton, protesting the broken global system that endangers us all.

The messages and manifestos delivered in the corralled ending of the protest - a safe distance from the dignitaries occupying the Sandton Convention Centre - made clear linkages between the hijacking of the sustainability and development agenda by corporate business and the pro-privatisation, free market, neo-liberal nexus and the intrusion of the elite on all of our lives and our world. It also linked and articulated the message of all classes, of intellectual and academic interests to those affecting the globally disenfranchised poor. These are essentially the same issues articulated by the occupy movement.

The status quo imperils us all. The middle class, the workers and the poor are squeezed for every cent like medieval serfs, bailing out crooked banks and a casino economy where only the rich win. In return we get to maintain a social safety net that simply keeps a lid on a pressure cooker, but fails to remove the source of fuel, oxygen or heat.

The poor see everyone as a problem, from foreign shop owners to middle class workers. To all external appearances all of those players are indistinguishable from either the one percenters or the charade of reality TV fed into everyone’s living room by corporate owned satellite feeds. The people are distracted by wrestling and soaps, misinformed by Fox and BSkyB.

More solidarity, communication and activism across the class divide is required if we are to move toward a commonly beneficial social construct capable of uniting civil society. After all, we have far more in common than we think. As the song goes, ‘A Luta Continua.’ Oh yes, and it is high time the cops come and join the protestors – we are on the same side, after all.

Posts by unregistered readers are moderated. Posts by registered readers are published immediately. Why wait? Register now or log in!

Really Important Piece

This article raises a crucial question: why is it that in Egypt, Turkey, Brazil etc the middle classes join with the poor against the 1% but here the middle classes join with the 1% against the poor. We are not going to get anywhere as a society until we work this out.

The Money System

One of the most important contributors to the negative conditions listed in this article is the way our money system is designed to operate. This is because dishonest money is indistinguishable from honest money and yet the money system enables dishonest money to be legally in circulation.

What is honest money as opposed to dishonest money?

I am deliberately using these terms in order not to get us involved in any discussions about counterfeit money.

Money is a human invention yes but the invention is only in the way chosen to externalise something that is already in existence.

This something is the intrinsic value that we, as individuals, accord to items that are of interest to us. These values

a) are in our heads

b) are rankings of the relative worths of the things of interest to us as indivuals, they do not need to be quantified in any way.

It is necessary however, in situations where we want to make voluntary exchanges of items with others, that the parties involved in an exchange accord within themselves, at least equal relative worths for the two items being exchanged, otherwise no voluntary exchange would take place. Note that it is within themselves that this equality needs to happen, whether the intrinsic values between the individuals need to be equal or not is irrelevant.

The above is only true in a situation of pure bartering however where actual goods and/or services are being physically exchanged. When money plays a role in the exchange process then the intrinsic values in the different individual heads have to be equal. This is because the intrinsic values have been quantified and externalised in the form of money.

It is therefore more than obvious that if money is to play an honest role in exchanges it must be a truthful representation of intrinsic worth. Thus honest money can be defined as the single, unique, external representation of the equal intrinsic values accorded to a specific exchangeable good or service by two or more individuals.

Dishonest money on the other hand is money purporting to represent such value when there are no goods or services the intrinsic value of which it can represent.

When dishonest money enters circulation is it treated by its first recipient as if it is honest money and therefore has the worth in terms of purchasing power that is stated on it. As it passes from user to user however its purchasing power falls as the market begins to realise that there is more money in circulation than real the intrinsic value available in real goods and services. We know this as inflation. Inflation does not effect the first users of dishonest money however consequently the current money system ensures that financial wealth continuously trickles up the financial pyramid giving rise to increasing social disease.